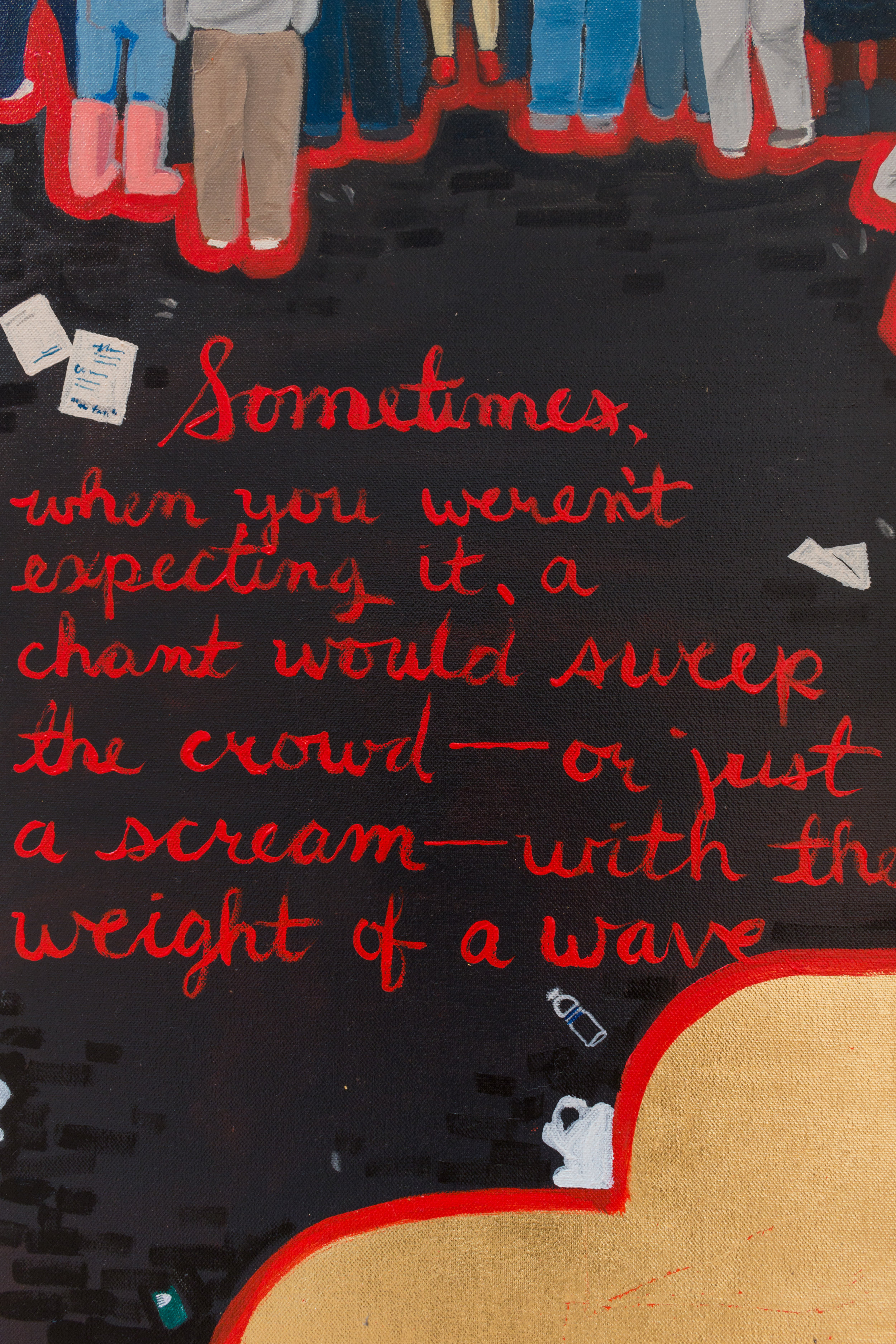

Self Portrait, 2017. Oil, gold leaf, and book cloth on canvas. 66" x 108".

On June 23rd, 2004, I was eight years old, and my parents bought new sand for my sandbox. That somewhere in the world a country was at war that day was of little interest to me. But coming to terms with identity—especially multicultural identity—is an ongoing exercise in looking beyond dichotomies of “us versus them”. It is to grow into a relationship with the world at large.

The Japanese folding screen, or byōbu, is an object that divides a room, but ties together artistic narratives from both East and West. Pairing traditional Japanese motifs with the European medium of oil on canvas, this screen-as-self-portrait serves as a symbol of a mixed race identity, and illustrates an interplay between one individual narrative and simultaneous global history. Its sides contrast the trajectory of my life, drawn from journals and photographs, with that of disastrous and influential scenes on the world stage. Each panel illustrates a moment in history witnessed by the artist, a character dressed in red. She travels through the development of both a multifaceted individual and global identity across the literal unfolding of time.